In truth, many incredibly tasty wines come from cooler climes. Case in point: Burgundy and Bordeaux, the famed regions of France, sit astride the so-called magic 45th parallel which puts them at nearly the same latitude as Oregon and Ontario’s wine-producing regions.

While you may have heard of Oregon’s luscious wines, you might not be as familiar with the increasingly sought after ice wines that trickle from the Niagara Peninsula in Canada. Jim Bernau, owner of Oregon’s

Willamette* Valley Vineyards, describes his state as one of the great wine regions—and the Niagara Peninsula is viewed similarly. What might have elicited suppressed giggles some years ago is rarely disputed today. In essence, cool climate wines are becoming increasingly, well, cool.

A Tale of TerroirAs Chicagoans continue their march through the world of wine, they’re discovering all the facets of that world, as if peeling an onion. And perhaps at the heart of the onion is terroir, the concept that the land and climate play as great a role in a wine’s taste as the grape itself or the efforts of the winemaker. A French word once the provenance of only sommeliers, ardent oenophiles and vintners, terroir crops up in publications with a frequency which would have been startling even ten years ago.

Nearly every wine expert I spoke with cited terroir as one of the defining characteristics of Oregon wine. In Pops for Champagne’s wine director W. Craig Cooper’s estimation, “The Willamette Valley is really the only New World region that has shown both the necessary dedication and the collective understanding of the varietal to allow this terroir to bloom.”

To the Willamette Valley’s Bernau as well as other local wine experts, the climate and land are ideal to produce three outstanding wines, pinot noir, chardonnay and pinot gris.

“The style we get from these soils and climate is delicate, well-balanced, feminine, food friendly wine,” Bernau explains. “Oregon pinot noir and pinot gris have a particular taste profile and aroma.” To the impassioned, pioneering winemaker, Oregon pinots have structure and balance and are eminently food friendly (which he claims is the reason they’re so popular in Chicago).

Pinot noir, which put the state on the map for wine-making, was first planted in the 1970’s. According to Jane Lopes of

Lush Wines, “Pinot noir is a fickle grape and requires a lot out of its growing conditions and its winemaker. It’s a risky grape to grow because it needs to ripen very slowly and a poor vintage—especially in the hands of a less talented or less detail-oriented winemaker—could be disastrous.”

A Warming TrendBernau believes that Oregon wines will only grow in popularity. “In Burgundy there’s no more space to plant more vineyards. They’d have to tear down houses. In Oregon, there’s plenty of land.” Moreover, he and more than 50% of Willamette Valley winemakers have certified sustainable operations in order to protect the environment.

“People aren’t just buying on quality and price,” he explains. “How can you possibly enjoy a glass of wine if you knew the environment was damaged in making it?” The Oregon vintners’ stewardship of the environment, as well as their Old World, craftsman’s approach to wines, have produced legions of fans in Chicago.

If you have the opportunity, visiting Oregon wine country has its own rewards. The antithesis of Napa, the Willamette Valley is mellow, laid back and infinitely more approachable. Just south of Portland, the scenic valley is full of low key wineries and impressive vistas.

The Coolest of Them All: The PinotAt first, pinot noirs were rather rare and could be difficult to find, and then came the movie Sideways. Now it’s one of the most popular wines, and Oregon—along with California—is one of the largest producers.

Bernau contrasts Oregon’s storied pinot noir with California’s as follows: “The California pinot noir is like the flashy girl you wanted to date but couldn’t bring home to mom. She’s voluptuous and wears a deep cut blouse. Oregon pinot noirs are elegant and wear a black evening gown. They’re the ones you want to take home to mom.”

Chris Cavarra, of

McCormick & Schmick’s, calls Oregon’s pinot noirs “phenomenal” claiming there’s no better wine to serve with salmon. “People think that you can’t drink wine with seafood,” he explains. “But pinot noir is very versatile and works.” The wine enthusiast also recommends Oregon’s pinot gris wines which he believes are an underappreciated wine and wonderful value.

An Even Cooler Cool Climate WineWhen I first heard about ice wine I have to confess that I wasn’t drawn to the stuff. With a moniker that’s not intuitive and two nouns that I’d learned should never go together, I was skeptical. I was celebrating at

Charlie Trotter’s with four long-time friends, when for our finishing course the waiter plunked down (well, delicately placed) glasses of a fine ice wine called Inniskillin.

Thankfully, the sommelier explained the almost syrupy, richly colored wine as he filled our petite wine glasses, and after I drained one glass, I wanted more. (But anyone who’s been to Trotter’s knows there no such thing as refills.)

It’s easy to regard the stuff as something for old ladies looking for an accompaniment for a bowl of bon bons, but ice wines—albeit sweet—are far too complex to be so quickly dismissed.

A Chilly PropositionGiven their price tags, ice wines might be identified with another ice—that found on engagement rings. What justifies the high price tags and lofty reputation of these golden nectars and are they worth it?

Creating ice wine is no easy feat. According to

Inniskillin’s Bruce Nicholson, a winemaker for 22 years, there’s little predictability. “With other grapes you know when they’re going to be harvested. With ice wine you never know. The temperature has to be at 18 degrees Farenheit or below for a prolonged period. And more often than not, that happens in the middle of the night.”

In other winemaking regions workers might pull long days, laboring to harvest the grapes during mild autumn days. At Inniskillin and with many ice wine producers, harvesting is done in the middle of the night during the dead of winter. And once the frozen grapes have been carefully harvested by bundled-up pickers, the work begins.

“The grapes are pressed right away,” he explains, to preserve the high concentrations of sugar in the fruit and to extract water in the form of ice crystals, leaving only a dribble of pure, concentrated nectar. (Talk about pulling an all-nighter.)

And if the challenge of harvesting the grapes and pressing them in the middle of a cold, dark Canadian night isn’t enough, there are myriad other potential threats. Because the ripe fruit must remain on the vine for three or four months, Mother Nature constantly threatens.

In 1983, Inniskillin’s crop was nearly obliterated by flocks of ravenous starlings, and in other years thaws or other weather extremes reduced harvests. Protective nets now cover vineyards, but freak thaws and high winds can still exact a toll. Nearly seven pounds of grapes are required in order to make one 376-milliliter bottle of ice wine—nearly a tenth of what the grapes would yield in regular wine.

Giving Ice Wines a Warm EmbraceTo Nicholson, all the effort and cold weather work are worth it. “Ice wines are something special,” he gushes. “The concentration of flavors is incredible.”

Describing ice wines as sweet is akin to saying the North Pole is chilly. While at first the thought of all that sugary liquid sluicing across your taste buds might foster a frown, the characteristics of the wine run more toward refreshing as opposed to cloying. Medium to full bodied, the wines are known for their long, lingering finish and intense, memorable flavors. The nose is often reminiscent of stone fruits, honey, citrus, figs and caramel, or even tropical fruits such as lychee. Even the color can be illustrative of its rich, nearly viscous lushness. Amber, honey or golden hued, the wines are imbued with seductive colors which are as beguiling as the drink itself.

Lush’s Lopes describes ice wine as “special because it’s such a difficult and risky proposition.” The unique process of allowing the grapes to freeze “concentrates the sugar and flavors, making for a sweet, rich dessert wine that is really unlike other sweet wines in its precision and intensity.”

Some Cold, Hard FactsIce wine is thought to have been first produced in 1794 in Germany when monks were surprised by an early frost. Making the most of their plight (and faced with a cold winter sans vin), the enterprising monks salvaged and pressed the grapes, discovering a rich, seductive nectar—the first ice wine.

While a number of countries produce ice wine, including Germany, Austria and the U.S., Canadian ice wines are the most highly regarded and most plentiful thanks to the ideal growing conditions of the Niagara Peninsula. Producers must follow Vintners Quality Alliance (VQA) regulations which stipulate, among other things, the sugar level of the grapes used to make the wine. Most wines are crafted from Riesling, Vidal, and Cabernet Franc, though makers are experimenting with other grapes and have also created sparkling versions. Typically sold in 375 or 200 milliliter bottles, the wines are meant to be sipped and not quaffed.

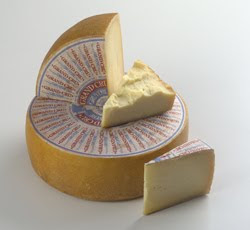

While the wine is often paired with dessert, it can just as easily be served with pungent cheeses or as an aperitif.

A Chilling ConclusionUltimately, whether it’s a crisp Oregon pinot gris, structured pinot noir or elegant, nectar-like ice wine, cool climate wines are climbing the charts.

Americans love affair with wine continues unabated and Chicagoans seem to create as many trends as they adopt. Maybe its because our climate is perfect for the consumption of all types of wines, or perhaps its stellar restaurants which demand wine that’s of equal variety and caliber. Bracing January evenings beg for a hearty red while scorching August days call for a refreshing pinot gris. So perhaps it only makes sense that cool climate wines have found a home in a cool city.

*While visiting an Oregon vineyard, I spotted a t-shirt on a staff person that read, “It’s Willamette, dammit,” which is a clearer and more expedient pronunciation guide than any I could dream up.

When Flavia Cueva returned to her family home outside petite Copan, Honduras, she was inspired. After having spent most of her life in the American Midwest, Cueva felt compelled to return to restore the decayed farmstead. Overlooking the ruins of an ancient Mayan city, the ideally situated farm seemed the perfect spot to create a small inn.

When Flavia Cueva returned to her family home outside petite Copan, Honduras, she was inspired. After having spent most of her life in the American Midwest, Cueva felt compelled to return to restore the decayed farmstead. Overlooking the ruins of an ancient Mayan city, the ideally situated farm seemed the perfect spot to create a small inn.