In the past decade or so our country’s consumption of top specialty cheeses has soared. In 1986 I first ventured to Europe and was perplexed to discover that many restaurants offered a cheese course for dessert. Cheese — for dessert? To sweet-toothed me, dessert always meant something sweet: an apple tart or chocolate fondant. It didn’t matter whether they called it fromage, queso or formaggio. To me, it just wasn’t dessert.

My hesitation was probably born of my experiences with American cheeses pre-1990 when bland and boring seemed to be the bywords for domestic production. These days my outlook has been altered. And based on the blooming abundance of distinctive cheese menus in restaurants around the city, I’m not the only one who's experienced a change of heart.

The great awakening

Twenty years ago or so Americans first discovered the joys of imported French and Italian cheeses such as brie and parmeggiano. At that time, it seemed difficult to find American-made cheeses that rivaled European counterparts. Since those days, a mushrooming bevy of craft cheese producing artisans have sprung up around the country from unlikely spots such as Louisiana and Indiana to more predictable states such as Vermont and Wisconsin. And the cheeses these Old World craftsman are creating are not just good for American cheeses, but have become considered damn good by international standards.

In the past decade or so our country’s consumption of specialty cheeses has soared. If ever there was a day when a Kraft Single ruled the land, those days are decidedly over.

So what brought Americans — and Chicago area residents, in particular — to this point?

Perhaps one explanation has been the popularity of wine. An excellent match for many cheeses, wine is as good a companion to cheese as chicken is to rosemary, pretzels to mustard and vanilla ice cream to hot fudge sauce. And given that the United States is now the second largest consumer of wine (after France), it only makes sense that we would go from nibblers of cheese to gobblers. Locally speaking, our metropolitan area is the second largest market for wine in the country, so perhaps it’s not surprising that premium cheeses are also to be found in great quantity. Finally, as we shun mass produced food oftentimes marked by inferior quality and unhealthful additives and often linked to environmental degradation, it’s only natural that we would seek something tastier and with more integrity when it comes to cheese.

Midwest is best?

Thankfully for Midwesterners, some of the finest cheeses are created right here. As American’s palates have grown more refined and adventurous, sparking a renewed interest in cheeses, producers in the area — as well as other major sources such as California and Vermont — have stepped up to the, er, cheese plate. Chicago stores and restaurants boast a great abundance and variety of premium and limited-production cheeses. Chicago’s Green City Market grows larger every year, and it seems as if there’s a back-to-the-land movement spawned by small-scale producers who prefer to earn a more modest income while producing award winning, high quality cheeses.

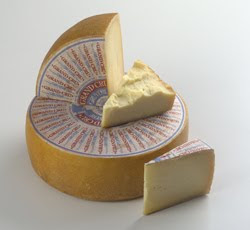

One of the best producers, Roth Käse, is located just across the border in Wisconsin. The company creates award-winning hard cheeses, such as gruyere which is known for its nutty, bold flavor, and many others. As with other small companies like petite Prairie Fruits Farm near Champaign, IL, which creates super-premium goat’s cheese, the products created end up on the tables of some of the finest restaurants in Chicago and elsewhere. And larger, but artisanal producers such as Carr Valley Cheese in LaValle, Wis., distribute their creations at finer grocery stores, specialty food stores, farmers' markets and on-line. Collectively, Wisconsin cheese producers receive the lion’s share of national awards, and for products ranging from traditional cheddar to hard ewes’ milk cheese.

One of the best producers, Roth Käse, is located just across the border in Wisconsin. The company creates award-winning hard cheeses, such as gruyere which is known for its nutty, bold flavor, and many others. As with other small companies like petite Prairie Fruits Farm near Champaign, IL, which creates super-premium goat’s cheese, the products created end up on the tables of some of the finest restaurants in Chicago and elsewhere. And larger, but artisanal producers such as Carr Valley Cheese in LaValle, Wis., distribute their creations at finer grocery stores, specialty food stores, farmers' markets and on-line. Collectively, Wisconsin cheese producers receive the lion’s share of national awards, and for products ranging from traditional cheddar to hard ewes’ milk cheese.

According to Bin 36’s Executive Chef John Caputo, local cheeses "are not only getting better, but also more sophisticated, both in flavor profiles and textures."

"One of my favorite local guys is Tony Hook and the ten-year cheddar he creates. Willi Lehner of Blue Mont Dairy seems to want to experiment with different techniques and methods in his brand new caves. And of course, I love the gruyere style cheese coming from Mike Gingrich at the Uplands Cheese Company."

In the case of Wisconsin’s much-in-demand Pleasant Ridge Reserve, the gruyere-style cheese is produced only in the summer and is featured in four-star restaurants. From one batch to the next, this rare cheese tastes different — but is always considered a masterpiece of culinary art.

Restaurants take a cue

A growing number of restaurants have installed cheese "caves" or refrigerators that store their precious cargo at an optimal temperature and humidity. Spiaggia's cave is one of the largest and probably the first in the city. Eno, at the other end of the Mag Mile, exists for customers to explore the almost magical flavor sensations experienced when pairing cheese and wine. Offering one of the most diverse collections around, the restaurant offers sheep, goat and cow’s cheese with the menu divided into smelly and pungent, triple cream, spicy, blue, hard and Wisconsin award-winners.

Standby Bin 36 offers an astounding 50 cheeses—available individually or as part of themed flights. Cheeses from Dallas, Indiana, Colorado and Louisiana sit inauspiciously beside listings for cheeses from France, Italy and Wisconsin. There are unusual selections here, and a brief but insightful insight into the character of each cheese.

Why all the cheese? According to Caputo, the menu represents "completely unique and totally sophisticated, well-produced cheeses."

Caputo is so devoted to cheese that he’s serving as the ambassador for Wisconsin's Milk Marketing Board for 2008. As if all of the excitement over cheeses in local restaurants were not enough, the American Cheese Society held its 25th anniversary conference in Chicago in July 2008. The fine dairy products juggernaut featured over 1,400 cheeses from around the country vying for coveted awards.

Other restaurants offer extensive cheese menus, including Pops for Champagne, which offers mostly American cheeses, including Cypress Grove and Old Chatham. Sepia, built from an 1890 print shop just west of the Loop, features an unusual, evolving artisan cheese cellar, stocking hard-to-find domestic creations such as Tarentaise from Vermont’s Thistle Hill Farm and Green Hill from Sweet Grass Dairy in Georgia, Berkshire blue from Massachusetts and Feliciana Nevat from Louisiana.

Most restaurants offer pairing suggestions for the cheeses they carry and Ontario-based ice wine producer Inniskillin recommends enjoying its elegant wines with Point Reyes Blue, Capricious goat cheese or Red Hawk from Cowgirl Creamery.

A labor of love

If you balk at the price you might pay for a premium cheese, consider that neither dairy farmers nor cheese producers rank anywhere near the top (or even bottom) of the Forbes richest list. For many, producing flavorful, unique cheeses represents a labor of love. The cheese they create, free of antibiotics, hormones or unnatural feed, tastes different from year to year, dependent upon what flowers and grasses the animals eat.

Artisanal producers, utilizing Old World, craftsman techniques, concentrate on quality over quantity, sometimes raising rarer Jersey cows which yield half the milk of traditional dairy bovines. Milk from Jersey cows produces tastier cheeses, and that, along with the animals’ diet and how they are treated, leads to more flavorful, richer tasting products.

As with the watershed Judgment of Paris in 1976 when American wine first bested French wine in a blind tasting, American cheeses are now winning international tasting competitions. To those who are just discovering the superb flavor and quality of American cheese, a bevy of domestic artisans, farmers and foodies merely ask, "What took you so long?"

My hesitation was probably born of my experiences with American cheeses pre-1990 when bland and boring seemed to be the bywords for domestic production. These days my outlook has been altered. And based on the blooming abundance of distinctive cheese menus in restaurants around the city, I’m not the only one who's experienced a change of heart.

The great awakening

Twenty years ago or so Americans first discovered the joys of imported French and Italian cheeses such as brie and parmeggiano. At that time, it seemed difficult to find American-made cheeses that rivaled European counterparts. Since those days, a mushrooming bevy of craft cheese producing artisans have sprung up around the country from unlikely spots such as Louisiana and Indiana to more predictable states such as Vermont and Wisconsin. And the cheeses these Old World craftsman are creating are not just good for American cheeses, but have become considered damn good by international standards.

In the past decade or so our country’s consumption of specialty cheeses has soared. If ever there was a day when a Kraft Single ruled the land, those days are decidedly over.

So what brought Americans — and Chicago area residents, in particular — to this point?

Perhaps one explanation has been the popularity of wine. An excellent match for many cheeses, wine is as good a companion to cheese as chicken is to rosemary, pretzels to mustard and vanilla ice cream to hot fudge sauce. And given that the United States is now the second largest consumer of wine (after France), it only makes sense that we would go from nibblers of cheese to gobblers. Locally speaking, our metropolitan area is the second largest market for wine in the country, so perhaps it’s not surprising that premium cheeses are also to be found in great quantity. Finally, as we shun mass produced food oftentimes marked by inferior quality and unhealthful additives and often linked to environmental degradation, it’s only natural that we would seek something tastier and with more integrity when it comes to cheese.

Midwest is best?

Thankfully for Midwesterners, some of the finest cheeses are created right here. As American’s palates have grown more refined and adventurous, sparking a renewed interest in cheeses, producers in the area — as well as other major sources such as California and Vermont — have stepped up to the, er, cheese plate. Chicago stores and restaurants boast a great abundance and variety of premium and limited-production cheeses. Chicago’s Green City Market grows larger every year, and it seems as if there’s a back-to-the-land movement spawned by small-scale producers who prefer to earn a more modest income while producing award winning, high quality cheeses.

One of the best producers, Roth Käse, is located just across the border in Wisconsin. The company creates award-winning hard cheeses, such as gruyere which is known for its nutty, bold flavor, and many others. As with other small companies like petite Prairie Fruits Farm near Champaign, IL, which creates super-premium goat’s cheese, the products created end up on the tables of some of the finest restaurants in Chicago and elsewhere. And larger, but artisanal producers such as Carr Valley Cheese in LaValle, Wis., distribute their creations at finer grocery stores, specialty food stores, farmers' markets and on-line. Collectively, Wisconsin cheese producers receive the lion’s share of national awards, and for products ranging from traditional cheddar to hard ewes’ milk cheese.

One of the best producers, Roth Käse, is located just across the border in Wisconsin. The company creates award-winning hard cheeses, such as gruyere which is known for its nutty, bold flavor, and many others. As with other small companies like petite Prairie Fruits Farm near Champaign, IL, which creates super-premium goat’s cheese, the products created end up on the tables of some of the finest restaurants in Chicago and elsewhere. And larger, but artisanal producers such as Carr Valley Cheese in LaValle, Wis., distribute their creations at finer grocery stores, specialty food stores, farmers' markets and on-line. Collectively, Wisconsin cheese producers receive the lion’s share of national awards, and for products ranging from traditional cheddar to hard ewes’ milk cheese.According to Bin 36’s Executive Chef John Caputo, local cheeses "are not only getting better, but also more sophisticated, both in flavor profiles and textures."

"One of my favorite local guys is Tony Hook and the ten-year cheddar he creates. Willi Lehner of Blue Mont Dairy seems to want to experiment with different techniques and methods in his brand new caves. And of course, I love the gruyere style cheese coming from Mike Gingrich at the Uplands Cheese Company."

In the case of Wisconsin’s much-in-demand Pleasant Ridge Reserve, the gruyere-style cheese is produced only in the summer and is featured in four-star restaurants. From one batch to the next, this rare cheese tastes different — but is always considered a masterpiece of culinary art.

Restaurants take a cue

A growing number of restaurants have installed cheese "caves" or refrigerators that store their precious cargo at an optimal temperature and humidity. Spiaggia's cave is one of the largest and probably the first in the city. Eno, at the other end of the Mag Mile, exists for customers to explore the almost magical flavor sensations experienced when pairing cheese and wine. Offering one of the most diverse collections around, the restaurant offers sheep, goat and cow’s cheese with the menu divided into smelly and pungent, triple cream, spicy, blue, hard and Wisconsin award-winners.

Standby Bin 36 offers an astounding 50 cheeses—available individually or as part of themed flights. Cheeses from Dallas, Indiana, Colorado and Louisiana sit inauspiciously beside listings for cheeses from France, Italy and Wisconsin. There are unusual selections here, and a brief but insightful insight into the character of each cheese.

Why all the cheese? According to Caputo, the menu represents "completely unique and totally sophisticated, well-produced cheeses."

Caputo is so devoted to cheese that he’s serving as the ambassador for Wisconsin's Milk Marketing Board for 2008. As if all of the excitement over cheeses in local restaurants were not enough, the American Cheese Society held its 25th anniversary conference in Chicago in July 2008. The fine dairy products juggernaut featured over 1,400 cheeses from around the country vying for coveted awards.

Other restaurants offer extensive cheese menus, including Pops for Champagne, which offers mostly American cheeses, including Cypress Grove and Old Chatham. Sepia, built from an 1890 print shop just west of the Loop, features an unusual, evolving artisan cheese cellar, stocking hard-to-find domestic creations such as Tarentaise from Vermont’s Thistle Hill Farm and Green Hill from Sweet Grass Dairy in Georgia, Berkshire blue from Massachusetts and Feliciana Nevat from Louisiana.

Most restaurants offer pairing suggestions for the cheeses they carry and Ontario-based ice wine producer Inniskillin recommends enjoying its elegant wines with Point Reyes Blue, Capricious goat cheese or Red Hawk from Cowgirl Creamery.

A labor of love

If you balk at the price you might pay for a premium cheese, consider that neither dairy farmers nor cheese producers rank anywhere near the top (or even bottom) of the Forbes richest list. For many, producing flavorful, unique cheeses represents a labor of love. The cheese they create, free of antibiotics, hormones or unnatural feed, tastes different from year to year, dependent upon what flowers and grasses the animals eat.

Artisanal producers, utilizing Old World, craftsman techniques, concentrate on quality over quantity, sometimes raising rarer Jersey cows which yield half the milk of traditional dairy bovines. Milk from Jersey cows produces tastier cheeses, and that, along with the animals’ diet and how they are treated, leads to more flavorful, richer tasting products.

As with the watershed Judgment of Paris in 1976 when American wine first bested French wine in a blind tasting, American cheeses are now winning international tasting competitions. To those who are just discovering the superb flavor and quality of American cheese, a bevy of domestic artisans, farmers and foodies merely ask, "What took you so long?"